suture needle size guide

Suture Needle Size Guide⁚ Understanding the Systems

Surgical suture needles employ two primary sizing systems⁚ the metric system, measuring diameter in millimeters, and the U.S. system, using a numbered gauge. Smaller gauge numbers correspond to larger needle diameters. Understanding both systems is crucial for selecting appropriate needles for various surgical procedures and tissue types.

Metric System vs. U.S. System

The selection of the correct suture needle size is paramount in surgical procedures. Two primary systems govern suture needle sizing⁚ the metric system and the U.S. system. The metric system offers a straightforward approach, directly indicating the needle’s diameter in millimeters (mm). For instance, a 0.01 mm needle is significantly finer than a 0.1 mm needle. This system provides a precise measurement, enhancing accuracy in needle selection. Conversely, the U.S. system utilizes a numbered gauge, creating a less intuitive scale. Smaller numbers in this system actually represent larger needle diameters. This inverse relationship can be confusing for those unfamiliar with the system, potentially leading to errors in needle choice. The U.S. system often uses a combination of numbers and zeroes (e.g., 6-0, 11-0), where a higher number of zeroes indicates a smaller diameter, adding to the complexity. Both systems are used in surgical settings, requiring healthcare professionals to be proficient in both to avoid misinterpretations and to select the optimal needle size for the specific surgical application. Choosing between these systems is often a matter of surgeon preference and institutional standards, though familiarity with both is critical for effective and safe surgical practices.

Needle Diameter and Gauge Number

Understanding the relationship between needle diameter and gauge number is fundamental to proper suture selection. The diameter, representing the needle’s thickness, directly influences its ability to penetrate tissue. Thicker needles, with larger diameters, are suitable for tougher tissues like skin, while thinner needles are necessary for delicate tissues such as blood vessels or internal organs to minimize trauma. The gauge number, used primarily in the U.S. system, inversely correlates with diameter. A smaller gauge number signifies a larger diameter needle, and vice-versa. For example, a 3-0 suture is thicker than a 6-0 suture. This inverse relationship can be initially confusing but becomes intuitive with practice. The metric system, which directly states the diameter in millimeters, offers a more straightforward representation. A 0.1 mm needle is considerably thicker than a 0.03 mm needle. Regardless of the system used, careful consideration of the needle diameter and its corresponding gauge number is essential for selecting the appropriate needle for the specific tissue type and surgical procedure. Accurate needle selection contributes to better surgical outcomes, reducing complications and promoting optimal wound healing.

Choosing the Right Needle Size

Selecting the correct suture needle size is paramount for successful wound closure. Needle size depends on tissue type and thickness; delicate tissues require smaller needles, while thicker tissues necessitate larger ones. Suture material also influences needle choice.

Tissue Type and Thickness

The type and thickness of the tissue being sutured are critical factors in determining the appropriate needle size. Delicate tissues, such as those found in ophthalmic surgery or microsurgery (e.g., blood vessels, internal organs, and the hand/nail bed), require very fine needles with small diameters (e.g., sizes 11-0 to 6-0). These smaller needles minimize tissue trauma and promote faster healing. Conversely, thicker tissues, such as skin or fascia, can tolerate larger needles (e.g., sizes 0-10). Larger needles provide sufficient strength to penetrate and effectively close the wound without excessive force. The goal is to achieve secure closure with minimal tissue damage. Using a needle that is too small for thick tissue can lead to increased trauma from excessive force, while using a needle that is too large for delicate tissue can cause significant damage and potentially compromise the healing process. Careful consideration of tissue characteristics is therefore essential for optimal surgical outcomes. The surgeon’s experience and judgment play a vital role in selecting the appropriate needle size for each specific tissue type and thickness.

Suture Material Considerations

The choice of suture material significantly influences needle selection. Different suture materials possess varying strengths and thicknesses, requiring needles designed to accommodate their physical properties. For instance, fine, delicate sutures like those used in ophthalmology (e.g., 11-0 to 6-0) often necessitate the use of correspondingly fine needles to prevent breakage or damage to the suture material. Conversely, thicker, stronger sutures such as those used for closing thicker tissues might require larger needles to ensure secure passage and grip. The needle’s swage, the point where the suture is attached, must also be compatible with the suture material; a poorly matched swage can result in suture slippage or breakage. The needle point type should also be considered in relation to the suture material. A sharp needle may be preferred for certain materials to minimize tissue trauma, while a blunt needle might be selected for others. Ultimately, the selection of a needle should always be guided by the combined characteristics of the suture material and the tissue type, ensuring a secure and effective closure while minimizing potential complications.

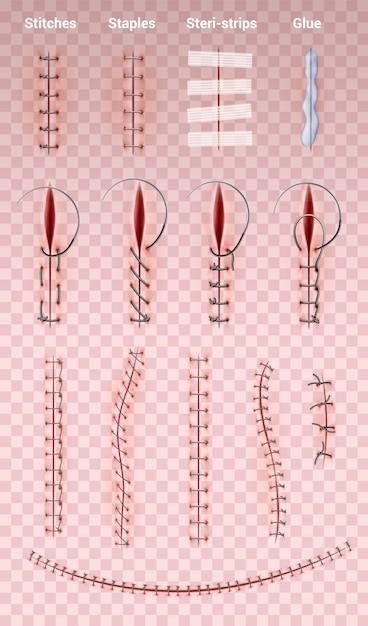

Needle Point Types and Their Applications

Surgical needles feature various point types, each designed for specific tissue types. Cutting needles create a precise incision, while tapered needles minimize tissue trauma. Reverse cutting needles facilitate easy passage through tough tissues. The choice of point type significantly influences surgical outcomes.

Penetration and Hole Size

The needle point is crucial in determining ease of penetration and the resulting hole size in the tissue. Different point types impact this significantly. Cutting needles, for instance, create a clean, precise incision, resulting in a larger initial hole but potentially more tissue trauma. Conversely, tapered needles create a smaller entry wound due to their gradual taper, causing less initial tissue damage, making them ideal for delicate tissues like blood vessels and internal organs. The size of the hole created also influences the suture’s grip and the overall strength of the suture line. A larger hole might compromise the tensile strength of the suture in the long term. The surgeon’s choice between cutting and tapered needles, therefore, depends heavily on the specific surgical context and the desired balance between ease of penetration and minimizing tissue trauma. The material of the suture itself can also affect the size of the hole, with thicker materials potentially creating larger holes even with thinner needles. Ultimately, the goal is to select a needle point that facilitates efficient suture placement while minimizing damage and ensuring a secure and durable suture line.

Swage and Suture Grip

The swage is the critical connection point where the suture material is attached to the needle. Its design significantly influences the suture’s grip and handling characteristics. A well-designed swage ensures a secure attachment, preventing the suture from slipping or detaching during the procedure. Microscopically, the swage often incorporates micro-teeth or other features that grip the suture material, enhancing its security. The strength and reliability of this connection are paramount, as suture slippage can compromise the integrity of the suture line. Different suture materials may require different swage designs for optimal grip, and the choice of swage type often depends on the specific suture material’s properties. For instance, a swage designed for a braided suture might not be ideal for a monofilament suture. The swage’s design also affects the overall needle’s handling. A poorly designed swage can make the needle difficult to control or manipulate. A secure swage, therefore, contributes to both the technical ease and the overall safety of the surgical procedure.

Suture Size Chart and Indications

This section details suture sizes, ranging from fine (11-0 to 6-0) for delicate procedures like ophthalmic surgery to larger sizes (0-10) used in thicker tissues. Each size is matched to specific surgical applications based on tissue thickness and strength requirements.

Sizes 11-0 to 6-0 and Their Uses

Sutures in the 11-0 to 6-0 range represent the finest sizes available, typically measured in millimeters with a diameter from approximately 0.01mm to 0.07mm. Their extremely small diameters make them ideal for microsurgery and delicate procedures where minimal tissue trauma is paramount. These sutures are frequently employed in ophthalmic surgery, where precision and minimal scarring are crucial for optimal visual outcomes. Their delicate nature also makes them suitable for intricate repairs of small blood vessels or delicate tissues such as those found in the hand or nail bed. The selection within this size range depends heavily on the specific surgical task, with smaller sizes (e.g., 11-0 and 10-0) reserved for the most minute and sensitive procedures, while slightly larger sizes (e.g., 7-0 and 6-0) find application in slightly more robust microsurgical repairs. The choice is determined by the surgeon’s assessment of the tissue’s fragility and the desired level of precision. The material used in these fine sutures also plays a role in their suitability for a given task, with certain materials offering better handling characteristics or strength retention than others.

Larger Suture Sizes (0-10) and Their Applications

Larger suture sizes, ranging from 0 to 10, denote progressively thicker and stronger sutures. These are used in situations requiring greater tensile strength and where tissue thickness necessitates a larger needle for effective penetration. Size 0 represents a relatively fine suture, often used in skin closure, while sizes 1-10 are employed for progressively thicker and tougher tissues or in situations requiring substantial holding power. Applications include closing larger wounds, securing substantial tissue masses, or performing procedures requiring significant strength during healing. The specific size chosen depends greatly on the tissue thickness, wound tension, and the surgeon’s assessment of the required holding power throughout the healing process. Factors such as the suture material’s inherent strength and its expected absorption rate also influence the size selection. For instance, thicker, non-absorbable sutures might be chosen for prolonged support in areas under significant tension, while smaller, absorbable sutures may be used in less-stressed areas where the body will eventually resorb the material.